2017 Workforce Data Revisions: Stronger Growth and Less Monthly Variability than Previously Indicated

Annual revisions to labor

force and nonfarm payroll jobs estimates have been published. Those revisions,

based on more complete data, indicate the unemployment rate was little changed

throughout 2017 and nonfarm payroll job growth was slightly stronger than

previously thought. Monthly data cited in this brief is seasonally adjusted.

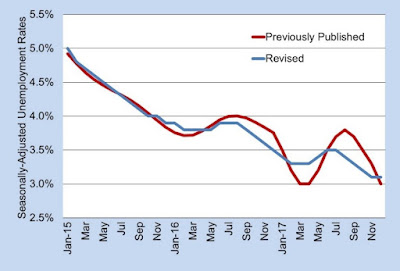

Unemployment Rate

Preliminary estimates,

released on a monthly basis throughout the year, indicated that unemployment

reached lows of 3.0 percent in the spring and at the end of the year, and highs

of 3.7 and 3.8 percent in the summer. Revised

rates indicate unemployment was not quite

as low or high – 3.3 percent in the spring and 3.5 percent in the summer,

ending the year at 3.1 percent in December. Given margins of error in the

survey sample, there was essentially no change in the unemployment rate last year.

The unemployment rate is the most well-known of six measures of labor underutilization. In 2017, all six measures reached new lows, including U-6, the broadest measure, which declined to 7.7 percent – the previous low was 8.2 percent in 2006. U-6 includes people who want a job but were not engaged in work search, those working part time who want full time work, as well the unemployed. (To be counted as unemployed an individual must have been available to work and engaged in work search. Retirees, students, homemakers, and other jobless people who are not actively searching for work are not considered unemployed – they are not in the labor force.)

Revised estimates now

indicate that unemployment was below 4 percent for 25 consecutive months

through December 2017. This is the longest period of such low unemployment

since the current estimating methodology was implemented in 1976, eclipsing the

previous long of 22 months from 1999 to 2001.

Revised Unemployment Rates are Smoother

The unemployment rate is the most well-known of six measures of labor underutilization. In 2017, all six measures reached new lows, including U-6, the broadest measure, which declined to 7.7 percent – the previous low was 8.2 percent in 2006. U-6 includes people who want a job but were not engaged in work search, those working part time who want full time work, as well the unemployed. (To be counted as unemployed an individual must have been available to work and engaged in work search. Retirees, students, homemakers, and other jobless people who are not actively searching for work are not considered unemployed – they are not in the labor force.)

All Six

Measures of Labor Underutilization

Reached

Series Lows in 2017

Nonfarm Payroll Job Growth

Monthly estimates throughout

the year indicated that nonfarm payroll growth averaged 4,400 jobs in 2017,

following a gain of 6,700 jobs in 2016. Revised data indicates stronger growth each

of the last two years: 4,500 jobs in 2017 and 7,600 in 2016. The average of

622,700 jobs in 2017 is an all-time high. The private sector averaged 522,600

jobs, a new high, and government averaged 100,100 jobs, close to 2015’s low

since 1999.

Private sector job gains in 2017 were primarily in the

healthcare and social assistance, leisure and hospitality, and professional and

business services sectors. Manufacturing jobs increased 300. After steady

losses over more than two decades that cut the number of jobs in half,

manufacturing has stabilized at just over 50,000 jobs for the last eight years.

Government jobs were little changed in 2017. Growth at the federal government-owned

Portsmouth Naval Shipyard offset continued declines in state government, now at

nine consecutive years. The three levels of government combined accounted for

16.1 percent of nonfarm payroll jobs, the lowest share since 1957.

The jobs recovery from the very deep 2008 and 2009 recession

has been driven by reductions in unemployment, as the size of the labor force

(employed plus job seekers) has been nearly unchanged for more than a decade. Maine

has an imbalanced population with far larger numbers of people in their 50s and

60s approaching retirement than young people who will enter the workforce. With

historically tight labor market conditions, reductions in unemployment are

unlikely to drive job growth going forward. In the years ahead, it will be

increasingly important that we attract young adults to move to the state in

order to maintain the size of our workforce.